I would never cycle in the rain for fun, luckily once in Argentina I feel the sun working as a super Prozac on my system. Six weeks cycling in the rain did me no good. But now, all is dandy again and cycling on the hardened mud track, not so long ago a mud pool, I feel life circulating through my veins.

The moon smiles it orange teeth at me, the cold wraps me in a clear starlit sky, the tent awakens covered in a sliver of ice and I embrace the absolute quietness in the vast pampas, exactly where I wanted to be. Even the fences are often gone, and this makes my sense of freedom complete. Streams are carrying plenty of water and the only necessity are hideouts to be protected from the relentless wind.

Every trucker on RN 260 receives my most peaceful smile and a feminine wave of my gloved hand. I talk to sheep and horses, and I sing with Natasha Atlas while the sharp wind pushes me as if it is a spring breeze.

Less than 100 kilometer distance from Chile and all circumstances have changed for the better. As if the sun is a button and I reset by it.

Cycling on ripio makes me slightly slower, I see so many things. I am shocked when I see three puppies choked to death, hanging on a fence. Having my thoughts going over the scene for long, I decide it is best for my peace of mind that it was a helpful deed of the person who did this, as many dogs suffer hunger and neglect. This way they might be better off. It has me thinking of a tribe who could kill their newborn baby within a certain time frame, to decide whether the child is without disabilities, healthy and able to cope with the harsh natural surrounding it is born in.

Meeting with the Ruta 40 again is seeing a signboard to Perito Moreno, my initial goal. I’m near but I am turning. It feels good, enough and satisfying though a bit nostalgic. I think of Chinese Daniel; he flew out from Puerto Montt to Torres del Paine and back, avoiding the rain. French Antoine with his three horses, one of them got sick, the other had a hoof infection, and were exchanged for one healthy horse, until this horse weakened, and he’d to abort his journey all together, never reaching the deep South.

The route on the paved roads becomes boring. Monotonous. I am in wonderment about so much no-thing. There really is not much out here. I get a fit when I see rhea’s. In the evening, when all the clatter is gone, I enjoy the silence and knowing of the space around me. There really is a lot of space.

A guanaco, related to a lama, watches me in utter vigilance.

Winter means starting the day of cycling at 12 while I stop, preferable, at 4 PM sharp. My meals consist of trashy food, resembling tinned cat food, pasta with added vitamines and always bell pepper, olives and tomato paste from a carton, which often leaks and has my stuff smeared in it. I get tired of it. Distances remain long without services.

The rain is exchanged for wind, usually coming from the North West, playing hard on my chest and slowing me down. When the sun is out, and the wind in my side, I am happy though. Daytime temperatures hover around 5 to 10 degrees when the sky is clear. Sometimes lower. In the night it freezes.

Yet, would I be in the Netherlands I would not dream of cycling and camping day after day…

It takes some time before I have undisturbed nights sleep again. The expensive Chinese mattress I bought bloated after 4 weeks. I bought a cheap Chilean brand and a crappy Chinese foam mattress. Both hurt my bottom and hip bones, making me turn throughout the night like a chicken on a broken, cold, grill.

It takes a good eye and practiced trespassing skills to sleep at lake Muster, but I succeed, without letting any cattle through the fences overnight. It is a heavenly quiet, soothing spot. I look forward to an undisturbed night sleep where I am far enough away to not hear the few passing trucks and cars.

In the middle of the night the wind swells and has my tent bulging over me. I get out in the cold crisp night and over think the two options: moving the tent to the skimpy tree or extracting the poles. The latter it will be and I continue to sleep on, with the tent cloth reeking moldy fluttering against my face.

At the end of a day with the wind in my back I am on the look out for a place to sleep, protecting me from the fierce wind. The few entry gates in the ‘return of the never-ending’ fences enclosing vast spaces are all closed and the two abandoned buildings are impossible to get access to. It is late, I want to stop. NOW! I try bending a broken fence so I can roll the bicycle over it. I’m hopeful; pushing the bicycle to the fence I sink deep into the muddy clay. I fall, the bicycle lands on top of me. The wheels get stuck and there is no movement whatsoever. I push the bicycle to the road, wheels blocked. To get the mud off would take much time, so I decide to camp next to the road instead. I haul the bicycle to the first bush I come upon. It’s a terrible spot (yet I have an excellent night sleep), people honk at me and I curse them!

I don’t really mean it. People are sweet in Argentina and I get more and more annoyed I don’t speak Spanish. In the supermercado a dusty old man dressed in brown corduroy halts me. He wants to know whether I like Argentina. We talk a bit. He pats my shoulder for being here. Same with four other people who see me, asking me whether it is not too cold, am I alone, going to Ushuaia? My conversations don’t go further than the basics, can’t even be called a conversation. I have to stop talking when I don’t understand them… I feel like a loner, while I really want to talk.

The route cuts straight through the country eastwards. From small places like Lago Blanco, Rio Mayo and Sarmiento, all similar in appearance. Sad, drab and excellent depression enhancers. The nature always struck me, although there is not much more to see than flat vastness. I notice my thoughts going to many places, except there where I am.

I cycle through immense oil fields where traffic becomes heavier. Most truck drivers and pick-up trucks sound their horn, give me thumbs up and wave frantically.

In order to protect myself against the wind I have little choice but to sleep again in a dip of the road, in front of a water channel tube. The oil fields are all fenced, closed and off-limits. The sun never reaches me and being it a minus 10 is not pleasant camping ground.

A cyclist I know via Messenger connects me to his friend living in Comodoro Rivadavia, the oil capital of the East Coast. The person I come to stay at is Martín, building a cabin in the so-called forest part of town.

Miraculously, while being lost in the steep going up and down typical South American grid where Martín’s supposed to live, I hear someone whistle. While I try to find Martín’s house, he finds me, standing on top of his house, where he oversees the sandy road carrying me.

I am happy to meet a person who has accepted my quest to be in his home. Martín departs in the evening, leaving me behind with Hector, a Chilean carpenter assist building his cabin. Hector hands me over the room he occupied, settling for the cold garage. I am dismayed with his exchange, insisting we arrange a second mattress for him to sleep in the small living room, together with cat Pinto.

I prepare soup from the few good examples of the rotten tomato-plants in Martín’s garden, covered by a plastic greenhouse. I prepare a lot of food, partly because Martín brings with him plenty. It seems he takes care for Hector, who seems to be living here.

Hector might be one of the many persons drifting through the continent in order to find work. Retirement funds don’t always apply and it dawns on me Hector has not much income.

Quite often, when I settle for a merry dinner, Hector knocks the door, returning from work. In South American culture, and pretty much every where in the world, big exception the Netherlands, people share whatever they have. And so, I split my meals, which I find a bit difficult, being mentally prepared to a huge festive food celebration. Soon after though, the happiness of seeing Hector enjoying his meals, settle me again.

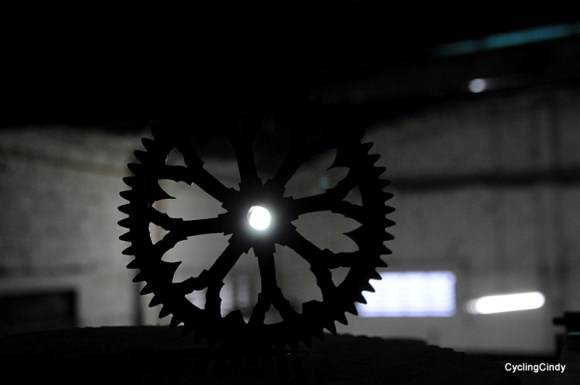

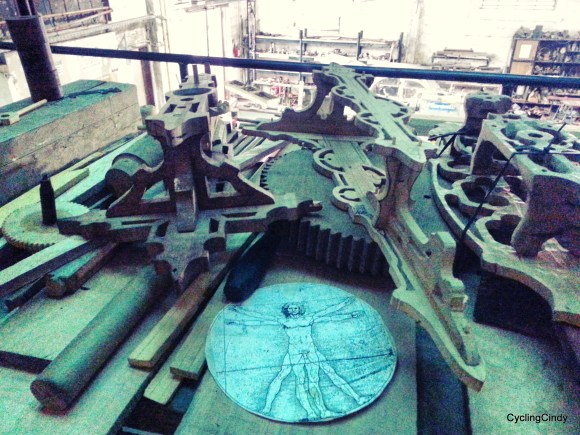

I await Martín when he arrives at siesta time and feel soothed in both his and Hector’s calm character. Hector and I keep our minds in happier places when he carves wood and I embroider. Hector is a true wood creator, he makes wall-clocks from wood, including the inside mechanism, lasting over a hundred years. ‘Working is my therapy,’ Hector says, and he works from early morning to late evening, in a factory which I visit.

Hector, in all those years he spend in Comodoro Rivadavia, teaching wood carving, he only visited the town center once, saying: ‘It is a depressing place with sorrowful faces walking around, I don’t like to be there.’ The use of marijuana and alcohol is not lower than in the Netherlands, to me it seems people here need a jump-start out of their daily wintry gloominess.

Martín tells me he is depressed too, the winter might have sunny days, all he does is working, from dawn to dusk. He looks eagerly forward to cycle the Carretera Austral, his few free weeks in the year.

The lack of WiFi and the shower not yet installed don’t bother me, the deficiency of my Spanish and never be able to have a normal conversation is working on my annoyance-level more than ever. Of course my vocabulary grows but with words alone I can not explain nor make myself clear. Martín buys me a dictionary, and suddenly, I am able to say more. Searching for the words in a book makes a conversation a slow process, and Martín, who comes to spend his siesta working in his garden, spend only time with me talking now.

The streets of Comodoro Rivadavia sighs with depression and sadness. People look awfully unhappy, some, unknowingly, add unappetising factors to it: like a fatty woman in black see-through stockings who bends over and wears a red G-string underneath. A force wind’s literally blowing over people. Worn out faces, gray buildings, immigrants and high prices in depressing supermercado’s. Many homeless dogs tally the streets where dissatisfaction and somberness has never been so obvious. Walking over to the supermercado feels like I am in a war stricken neighborhood, it is more ugly than most area’s in Afghanistan. Maybe it is the mud flood that has clogged the streets. It is not that the people are to blame, it are the clouds, the cold, the winter, says Martín. And I could not agree more.

Come to think of it, those same feelings occurred when I got stuck for months in an active civil war in Kashmir. Post-war Afghanistan with its weekly bomb blasts did me no good either. I never thought I could add Patagonia to the list of depressive places. But here it is: Patagonia number three of awful places.

My feelings, bordering depression, are slightly moving towards the positive level but are still too dark. I know the clouds, the cold and the fierce wind is to blame. Although I still want to cycle, I absolutely do not want to cycle from Comodoro Rivadavia to Buenos Aires. With the wind almost frontal! Without services for 200 kilometer! You must be kidding! A truck it will be!

Avoiding paid accommodation was a relative easy task, and sailing with the wind towards the winter was easy enough too. But being in the winter, caught in snowy conditions not occurred since decades, not being able to communicate and eat properly, sleeping on bone-hurting mattresses, confined to a tent, unable to move in a zipped down sleeping bag, rain and clouds; it left traces. I knew something would come my way, tear me loose from the high peak I was bobbing on…

Now I am in Patagonia, where people are delirious about, and deeper down in Patagonia I am sure it is packed with natural abundance, but that is not where I am. I am in an oil town, in winter, and have zero desires to go out and about. I wonder when I will have the power to decide to haul my bags down the ladder, strap them on the bicycle racks and leave for the rotunda where I will search for a truck to Buenos Aires?

I would love to cover the windows with thick velvet curtains, so I won’t see the dark green trees waving against the gray. I would love to eat from Martín’s garden only, except that there doesn’t grow much in winter. I prefer not to enter supermercado’s because the people in it appear brain-dead and utterly unhappy with living in an oil town in Patagonia.

But of course, gradually, I realize I can’t stay the whole winter at Martín’s den, even though I would love to. The celestial long nights on the mattress in my own private room Hector offered me are way better than in the closed, claustrophobic sleeping bag. Cooking is way handier on an actual stove in a standing position. The evenings where I embroider and Hector carves wood are warm, as we have electric heating.

I am loving the days where Martín, Hector and I work, each separately but all for Martín’s lovely little house. I realize again, that this is what I wanted for long: manual work in a small community, that the bigger goal is lacking is a detail.

It is hard to leave. To load the bicycle and cycle out to the roundabout to catch a truck. It is hard to leave the comfort, however little and leave an ugly oil town behind. It is hard to go out and make photographs even.

But then, on a windy Tuesday I feel it is a good day to leave. Martín brings me to the roundabout in his car, something I am very happy with as I really dread every rotation of the bicycle pedals in Patagonia.

I think it is a great lie to state you like cycling in the cold, windy, iciness of Patagonia or wherever on Earth. Without being indoors, and for a long period of time, it is not fun, not nice and not comfortable. People who state they love riding in such conditions I suspect what they mean is something different. They might enjoy the after-bliss of the great challenge, but not the actual time-being in that very moment.

Another discovery is that I do not really mind my lack of Spanish, because even would I be able to speak more, I still miss the ability to make a conversation on a deeper level. I have come to realize that what I need is connection. Pleasant and extremely caring, tranquil and company seeking, Martín and Hector met me as their lonesome sister. Undeniable, the Patagonian cold lays its froth upon the folks born here. The person I meet within 10 minutes after Martín hugs me goodbye is not a Patagonian born…

Martín, I thank you for your great hospitality (and the asado). It did warm me up well in the Patagonian coldness. Thank you Claudia (Martín’s partner), for presenting me embroidery threads.

More info about numbers and details here

July 2017

4 replies on “The Big Depressing Patagonian Fuss”

[…] post 8: The Big Depressinig Patagonian […]

LikeLike

As always, I enjoy your photography and the pictures you paint with your prose. Thanks for sharing your travels and experience.

LikeLike

And thank you for writing such a kind compliment. I’m glad you enjoyed this post and I promise the next will be positive again.

LikeLike

[…] Although a born Patagonian the low hanging clouds, the forever grayness and dead silence made him depressed as well but gardening balanced his mood back to a fine […]

LikeLike